Cybersecurity researchers on Thursday disclosed two distinct

design and implementation flaws in Apple’s crowdsourced Bluetooth

location tracking system that can lead to a location correlation

attack and unauthorized access to the location history of the past

seven days, thereby by deanonymizing users.

The findings[1]

are a consequence of an exhaustive review undertaken by the Open

Wireless Link (OWL) project, a team of researchers from the Secure

Mobile Networking Lab at the Technical University of Darmstadt,

Germany, who have historically taken apart Apple’s wireless

ecosystem with the goal of identifying security and privacy

issues.

In response to the disclosures on July 2, 2020, Apple is said to

have partially addressed the issues, stated the researchers, who

used their own data for the study citing privacy implications of

the analysis.

How Find My Works?

Apple devices come with a feature called Find My[2] that makes it easy for

users to locate other Apple devices, including iPhone, iPad, iPod

touch, Apple Watch, Mac, or AirPods. With the upcoming iOS 14.5,

the company is expected to add support for Bluetooth tracking

devices — called AirTags[3]

— that can be attached to items like keys and wallets, which in

turn can be used for tracking purposes right from within the Find

My app.

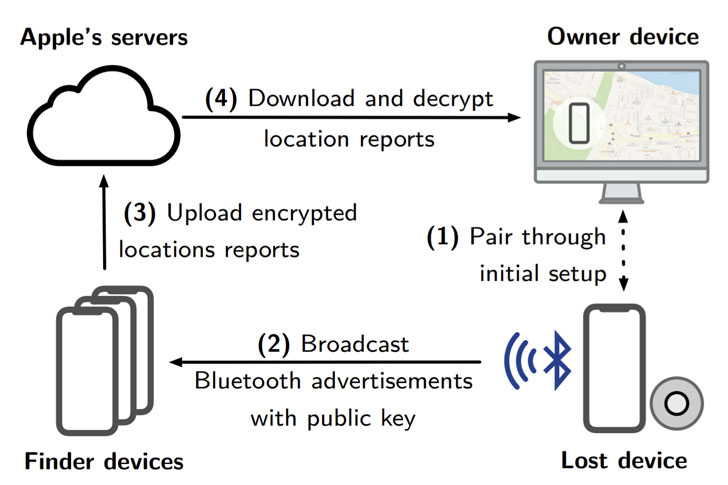

What’s more interesting is the technology that undergirds Find

My. Called offline finding and introduced in 2019, the location

tracking feature broadcasts Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) signals from

Apple devices, allowing other Apple devices in close proximity to

relay their location to Apple’s servers.

Put differently, offline loading turns every mobile device into

a broadcast beacon designed explicitly to shadow its movements by

leveraging a crowdsourced location tracking mechanism that’s both

end-to-end encrypted and anonymous, so much so that no third-party,

including Apple, can decrypt those locations and build a history of

every user’s whereabouts.

This is achieved via a rotating key scheme, specifically a pair

of public-private keys that are generated by each device, which

emits the Bluetooth signals by encoding the public key along with

it. This key information is subsequently synchronized via iCloud

with all other Apple devices linked to the same user (i.e., Apple

ID).

A nearby iPhone or iPad (with no connection to the original

offline device) that picks up this message checks its own location,

then encrypts the information using the aforementioned public key

before sending it to the cloud along with a hash of the public

key.

In the final step, Apple sends this encrypted location of the

lost device to a second Apple device signed in with the same Apple

ID, from where the owner can use the Find My app to decrypt the

reports using the corresponding private key and retrieve the last

known location, with the companion device uploading the same hash

of the public key to find a match in Apple’s servers.

Issues with Correlation and Tracking

Since the approach follows a public key encryption (PKE[4]) setup, even Apple

cannot decrypt the location as it’s not in possession of the

private key. While the company has not explicitly revealed how

often the key rotates, the rolling key pair architecture makes it

difficult for malicious parties to exploit the Bluetooth beacons to

track users’ movements.

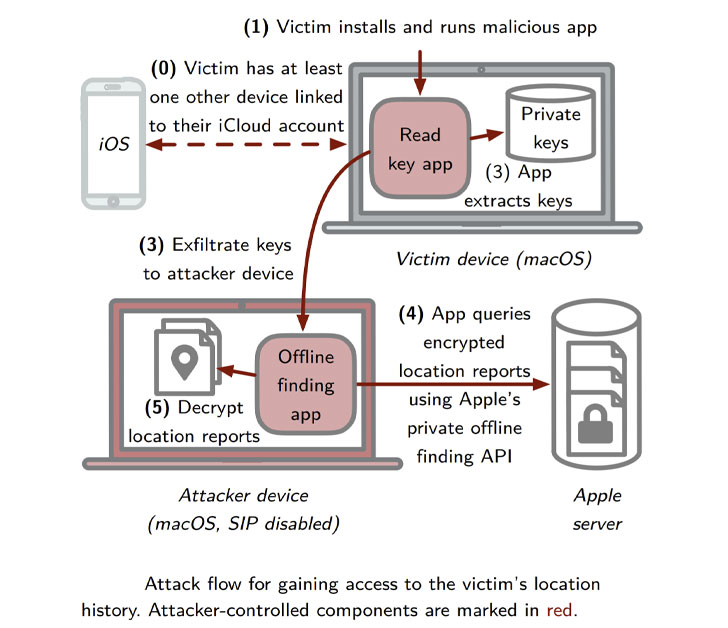

But OWL researchers said the design allows Apple — in lieu of

being the service provider — to correlate different owners’

locations if their locations are reported by the same finder

devices, effectively allowing Apple to construct what they call a

social graph.

“Law enforcement agencies could exploit this issue to

deanonymize participants of (political) demonstrations even when

participants put their phones in flight mode,” the researchers

said, adding “malicious macOS applications can retrieve and decrypt

the [offline finding] location reports of the last seven days for

all its users and for all of their devices as cached rolling

advertisement keys are stored on the file system in cleartext.”

In other words, the macOS Catalina vulnerability (CVE-2020-9986)

could allow an attacker to access the decryption keys, using them

to download and decrypt location reports submitted by the Find My

network, and ultimately locate and identify their victims with high

accuracy. The weakness was patched by

Apple[5] in November 2020

(version macOS 10.15.7) with “improved access restrictions.”

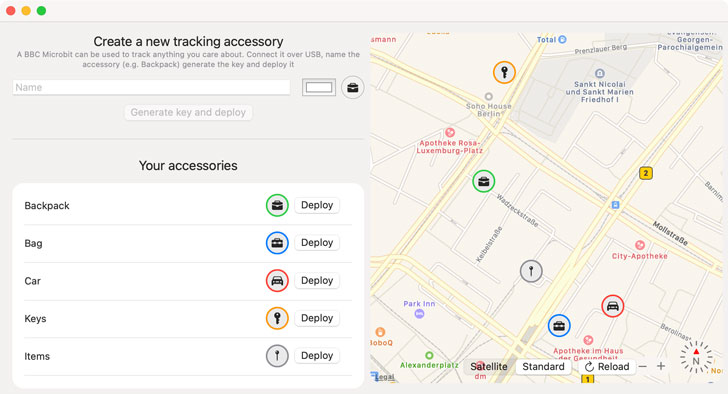

A second outcome of the investigation is an app that’s designed

to let any user create an “AirTag.” Called OpenHaystack[6], the framework allows

for tracking personal Bluetooth devices via Apple’s massive Find My

network, enabling users to create their own tracking tags that can

be appended to physical objects or integrated into other

Bluetooth-capable devices.

This is not the first time researchers from Open Wireless Link

(OWL) have uncovered flaws in Apple’s closed-source protocols by

means of reverse engineering.

In May 2019, the researchers disclosed[7]

vulnerabilities in Apple’s Wireless Direct Link (AWDL) proprietary

mesh networking protocol that permitted attackers to track users,

crash devices, and even intercept files transferred between devices

via man-in-the-middle (MitM) attacks.

This was later adapted by Google Project Zero researcher Ian

Beer to uncover a critical “wormable” iOS

bug[8] last year that could

have made it possible for a remote adversary to gain complete

control of any Apple device in the vicinity over Wi-Fi.